Invasive Terrestrial Plants

Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum)

Giant hogweed is a large, sturdy, noxious weed that has been introduced to the United States. Typically growing to heights 6 to 16 feet and resembling Common Hodweed, giant hogweed causes phytophotodermatitis and is considered extremely toxic. Phytophotodermatitis results from contact with the sap of the giant hogweed plant (followed by exposure to sunlight or UV rays), and results in blisters, long lasting scars, and blindness (if it comes in contact with the eyes).

As mentioned above, one of the most distinguishing features of giant hogweed is its enourmous size and large, umbrella shaped, white flowering head. The stout, reddish-purple stems are hollow and the deeply incised compound leaves can grow 3-5 feet in width. Giant hogweed is extremely dangerous. If you find a plant growing you should contact the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation. The NYS DEC has a giant hogweed control program with trained field crews that will safely remove giant hogweed from your property

FREE OF CHARGE! Call the giant hogweed hotline at (845) 256-3111 or visit their website here.

Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria)

Purple loosestrife is an hardy, upright, perennial herb that may grow up to 7 feet tall. It developes a strong taproot and may have up to 50 stems arising from its base. When in bloom, loosestrife exhibits showy purple flowers that some find aesthetically pleasing. This plant is highly invasive, and is commonly found in monocultures where it has infested. Purple loosestrife provides few nesting materials for wildlife, little food, poor cover, and causes annual wetland loss of 190,000 hectares in the United States. In many areas where its populations have increased, wildlife species have declined causing major changes in wetland communities.

Many considerations need to be taken into account with regards to controlling purple loosestrife. Due to the prolific seed production and ease at which the seeds are dispersed, individuals should contact their local agricultural extension specialist or county weed specialist to learn what control methods work best in their area. Purple loosestrife can also spread vegetatively by resprouting from stem or rootstock cuttings; cuation must be exercised when considering manual or mechanical control methods. This plant is currently in decline in the US due to successful biocontrols.

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata)

Garlic mustard is a biennial flowering plant with a triangular to heart-shaped leaves that, when crushed, smell like garlic. Flowering during the spring and summer, a single plant is capable of producing hundreds of seeds, with seeds remaining viable in the soil for up to five years.

Garlic mustard was introduced to North America in the mid 1800’s as a culinary herb. Insects and fungi that normally feed on garlic mustard are not present in North American, which allows the plant to increse its seed production. Once introduced to an area, garlic mustard out-competes native plant species for light, moisture, nutrients, soil, and space. As garlic mustard replaces these native plant species, many insects and animals are deprived of esssential food sources.

Since the seeds of the garlic mustard plant can remain viable in the soil for five years, effective management will require long term commitment and monitoring. For smaller infestations hand pulling and physical removal should be used if possible. Since new plants can sprout from root fragments, care must be taken to ensure that the entire root system is removed. For larger scale infestaions, flowering stems can be cut at ground level (or several inches above the ground) to prevent seed production.

Japanese Knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum)

Japanese Knotweed is a perennial, herbaceous shrub that grows up to 5 meters tall. It has hollow, bamboo-like shoots that are segmented. Stems are red or orange. Japanese knotweed grows in dense clusters that shade out light, preventing other plant growth. The stems die back each growing season, while extensive underground stems (known as rhizomes) can survive for decades.

Native to Asia, Japanese Knotweed was introduced to North America for ornamental use in the 1870’s. Populations can be found throughout the entire state of New York. Knotweed is adapted to a wide variety of soild types and pH levels, and can be found growing along riverbanks, wetlands, distrubed areas, roadsides, woodlands, and grasslands.

Populations of Knotweed out-compete native plants for light and nutrients; forming dense, tall stands that prevent light from reaching the ground. With growth rates of up to 8cm a day, by emerging in early April Knotweed can outcompete native species for light resources. In addition, knotweed clogs ditches, break up pavement, and destroys flood control structures. Once established, knotweed is extremely difficult to control and eradicate. Early deterction and removal of small patches is advised. Manual removal is effective on small infestations, while mechanical and chemical controls may be required for large infestations. Populations and infestations should be reported to the National Invasive Species Hotline at: 1-877-STOP-ANS (1-877-786-7267)

Slender False Brome (Brachypodium sylvaticum)

Slender False Brome (also known as false is a highly invasive perennial bunch grass native to Eurasia and North Africa. This species grows 12 to 18 inches high with flat leaves 1/4 to 1/3 inch wide. Slender False Brome can thrive in a variety of ecological conditions but is most abundant in woodlands and open grasslands. It is easily spread through seed and forms dense stands, preventing native species from germinating and growing. Even though it grows in abundance, Slender False Brome doesn’t provide a food source to wildlife and livestock due to its low palatability.

Unlike other grass species, a prescribed burn cannot be used to remove Slender False Brome. In isolated small patches, it can be dug out before it reaches seed. In large patches, the best removal technique is a combination of mowing in early July before it goes to seed followed by an herbicide treatment in the fall. Removal effort require follow up in order to be successful.

Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica)

Originally from Japan, Japanese Honeysuckle was introduced to the UnitedStates as an ornamental plant in the early 1900s. Since then, this deciduous to semi-evergreen woody vine has successfully colonized  successional fields, roadsides, forest edges and fencerows.This honeysuckle usually grows 80-120 feet long and has fragrant flowers that fade from white to yellow and bloom in late spring. Berries are small and black. Japanese Honeysuckle’s wide habitat adaptability, rapid growth rate and extended growing season make it a tough competitor against native species. It is able to displace native species by outcompeting them for light, water and nutrients. The vines of honeysuckle twine around native trees and shrubs eventually causing them to collapse. This species also forms dense thickets, shading out the understory layer and preventing new native species from growing. Small infestations of honeysuckle can be removed by hand-pulling but all plant material must be removed to prevent regrowth.

successional fields, roadsides, forest edges and fencerows.This honeysuckle usually grows 80-120 feet long and has fragrant flowers that fade from white to yellow and bloom in late spring. Berries are small and black. Japanese Honeysuckle’s wide habitat adaptability, rapid growth rate and extended growing season make it a tough competitor against native species. It is able to displace native species by outcompeting them for light, water and nutrients. The vines of honeysuckle twine around native trees and shrubs eventually causing them to collapse. This species also forms dense thickets, shading out the understory layer and preventing new native species from growing. Small infestations of honeysuckle can be removed by hand-pulling but all plant material must be removed to prevent regrowth.

Pale Swallow-wort (Cynanchum rossicum) & Black Swallow-wort (Cynanchum rossicum)

Both members of the milkweed family, Pale (right) and Black (left) Swallow-wort are perennial vines that climb 1-2 meters. The stems climb up other plants, twining together and forming ropes. These plants have ovalleaves that turn golden yellow in late summer. Narrow, pointed seed pods disperse seeds in late July to September. Pale Swallow-wort has pale pink to reddish brown flowers and Black Swallow-wort has dark purple to almost black flowers, both open in mid-May to July, peaking in early June.

Native to the Ukraine and southwestern Russia, these Swallow-worts were first recorded in New York in  1897 in Monroe and Nassau Counties. Currently, Paleand Black Swallow-wort are known to occur in 21 states across the northeastern and mid-western United States and in Canada. These species are adapted to a wide range of light and moisture, and can be found growing in fields, woodlands, river banks, disturbed araes, and shallow soils.

1897 in Monroe and Nassau Counties. Currently, Paleand Black Swallow-wort are known to occur in 21 states across the northeastern and mid-western United States and in Canada. These species are adapted to a wide range of light and moisture, and can be found growing in fields, woodlands, river banks, disturbed araes, and shallow soils.

Populations of Swallow-wort out-compete native plants for resources; forming dense stands the reduce plant and animal biodiversity. Swallow-wort changes the ecology of the soils, displacing other plants. Monarch butterflies lay eggs on Swallow-wort, mistaking it for milkweed. The monarch larvae don’t survive because they can’t feed on the swallow-wort. This plant is also toxic to livestock and wildlife. A combination of manual, mechanical, and chemical controls may be neccessary depending on the size of the infestation. Populations and infestations should be reported to the National Invasive Species Hotline at: 1-877-STOP-ANS (1-877-786-7267)

Asiatic Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus)

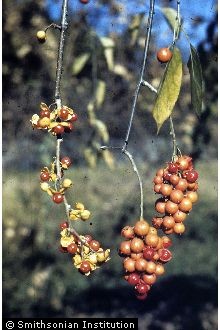

Asiatic bittersweet, also known as Oriental Bittersweet, is a perennial, woody vine that can climb up to 18 meters. This species will also twine about itself, forming dense patches. Green, nearly round leaves turn golden yellow in late summer to fall. Green, round fruits turn bright yellow in the late summer or early fall. Seed dispersal is primarily through birds and small mamals. Flowers open from May-June, and are greenish-yellow in color.

Native to Japan, Korea, and China, Asiatic Bittersweet was introduced to North America in the 1860’s. In 1897 it was introduced to the New York Botanical Gardens. Asiatic Bittersweet is currently distributed in 27 states; from Maine to Louisiana, and west to Missouri. This species can be found growing in fields, forest edges, woodlands, disturbed areas, meadows, roadsides, and coastal areas.

Populations of Asiatic Bittersweet pose a threat to all plant types in open and forested areas. As the vines grow over other plant species it kills them by shading out light, consticting growth, and uprooting. Trees that have been overtaken by Asiatic Bittersweet are more susceptible to wind and ice damage; posing greater hazards to life and property. As vines overtake an area wildife is oftern displaced, especially bird species. An integrated approach is oftent he most effective when dealing with infestations of Asiatic Bittersweet. Populations and infestations should be reported to the National Invasive Species Hotline at: 1-877-STOP-ANS (1-877-786-7267).

Phragmites (Phragmites australis)

Also known as common reed, phragmites is a wetland plant species that is found in every U.S. state. Growing up to 6-12 feet high, it forms dense stands and is a long-lived species. The seedhead is purplish or tawny with a flaglike appearance. Phragmites is commonly identified by its height.

Widely distributed, Phragmites is found ranging all over Europe, Asia, Africa, American, and Australia. Both native and introduced genotypes exist in North America. Growth starts in February in some locations, with flowers developing by mid-summer. Seed set occurs through fall and winter, with seed germination occuring in the spring on exposed moist soils. Phragmites also forms a dense network of underground roots which send out rhizomes allowing the plant to spread horizontally.

An excellent colonizer, Phragmites can form dense, monoculture stands that outcompete other native plant species. Wetland hydrology and wildlife can be altered adversely, and the increased biomass of dead grass can increase fire potential. Integrated pest management can involve chemical, physical, and biological controls. Phragmites cannot withstand heavy, prolonged grazing.

Japanese Angelica Tree (Aralia elata)

First detected in Monroe County in October of 2019, not much is currently known about the impacts that angelica tree may have on our ecosystems. What we do know about angelica tree is that it grows quickly and prolifically, having its seeds dispersed by birds and being able to root sprout when the above ground trunk is killed. This tree has long alternate compound leaves (15-48″) with many prickles on its branches, and sometimes even the leaves and leaflets. It can reach anywhere from shrub size to 40′, and has white flowers in late summer that produce small black berries in fall. This tree looks almost exactly like our native Devil’s Walkingstick (Aralia spinosa), with the key identifier being the lack of a main central axis stalk in the infloresences. Other identifiers are smaller flowers, smaller berries, and leaf margins on Devil’s Walkingstick compared to angelica tree. So far, angelica tree has been present in Mendon Ponds and Durand Eastman Parks in Monroe County.

Callery Pear (Pyrus calleryana)

Also known as Bradford pear, this tree has been a popular ornamental for years. It’s impacts as an invasive species and negative effects against native species are only just being realized. Commonly seen in parking lots, parks, and other large public places, Callery Pear spreads and establishes fast, creating dense populations shading out any native species that were previously there. These trees grow to be 50 feet tall and 30 feet wide with small, leathery leaves. The main way to ID Callery Pear from other similar looking plants is it’s symmetrical growth pattern. The other main ID characteristic is the round five-petaled small white flowers, distinguishing it from dogwoods or cherry trees. Callery Pear flowers very early, before any native species in Monroe County, and in turn leaves are out very early too and remain well through the fall. This is what makes this tree easily outcompete native species.

For a full list of invasive terrestrial plants in or around our region, see the FL-PRISM terrestrial plant list: http://fingerlakesinvasives.org/species_types/terrestrial-plant/